What is JPA?

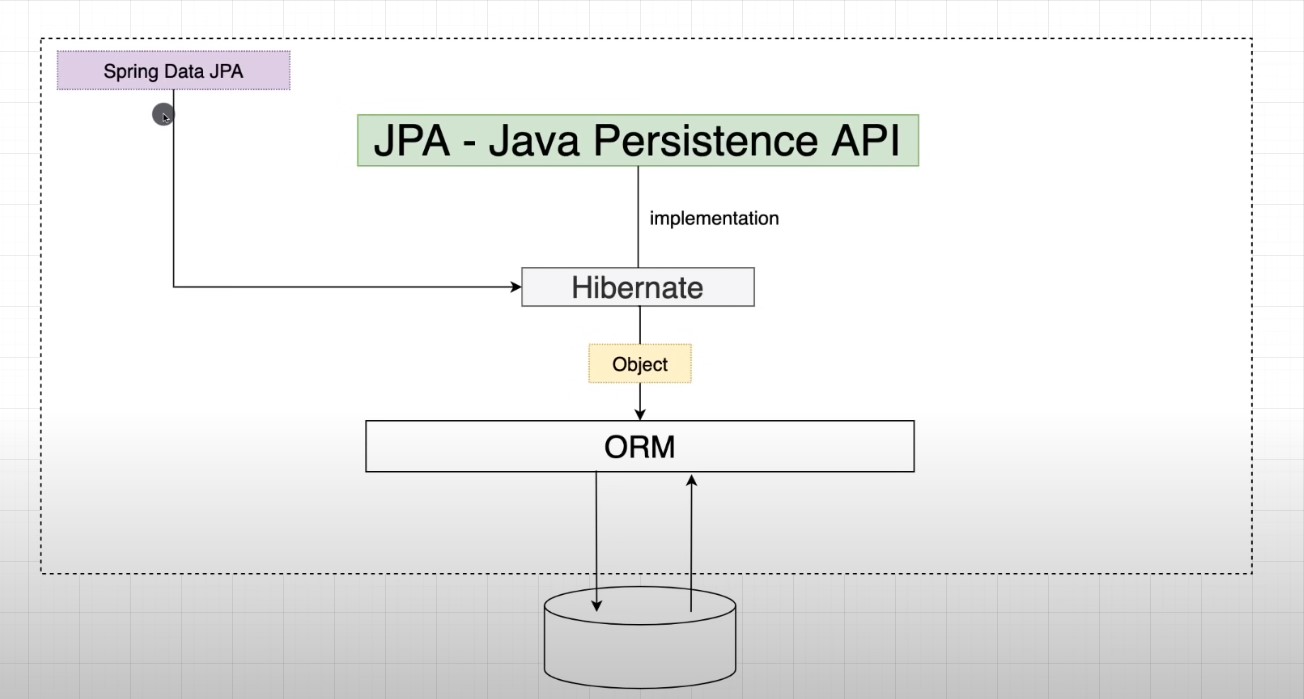

JPA, which stands for Java Persistence API, is a specification for persisting data with Java objects. (Persistence means that the object is stored in a database). JPA has multiple implementations, the most popular being Hibernate. Hibernate is an ORM tool. ORM, or Object Relational Mapping, maps a Java object to a database. This allows us to do CRUD operations (create, read, update, and delete data) on the object.

Note that Spring Data JPA and JPA are two different things. Spring Data JPA abstracts JPA. It reduces the amount of boilerplate code that programmers have to write by providing repositories for CRUD operations. This means that SQL knowledge isn’t required to work with Spring Boot. However, knowing SQL can help you perform more powerful queries.

Below is a helpful visualization of the relationship between JPA, Spring Data JPA, Hibernate, and ORM (credit to Amigoscode):

Setup

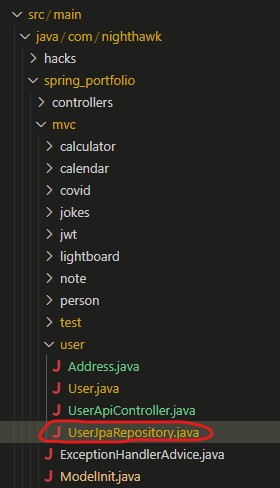

Within the mvc folder in spring_portfolio, create a new folder and give it a name. The new folder will hold the POJO (entity class), API controller, and JPA repository. You can name the files anything, but the convention for JPA repository is to include JpaRepository or Repository within the name. In this example, the JPA repository file is named UserJpaRepository.java.

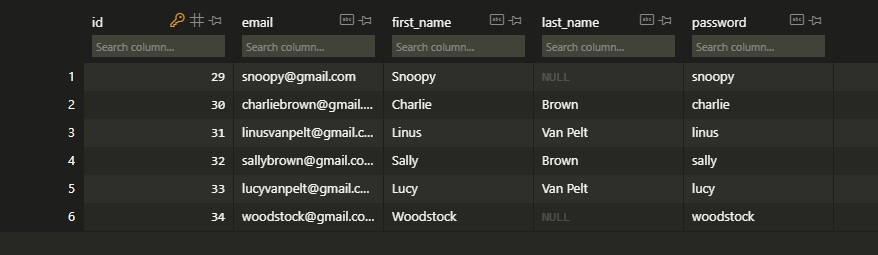

This blog will use a user database as an example. For reference, this is what the User POJO (User.java) looks like. Attributes of the user include the user’s email, password, and name. Note that there are lots of annotations (the lines that start with a @) that can add more features to the attributes.

@Data

@AllArgsConstructor

@NoArgsConstructor

@Entity

public class User {

@Id

@GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.AUTO)

private Long id;

private String email;

private String password;

private String firstName;

private String lastName;

}

This is what the user table looks like:

There are many ways to perform CRUD operations in Spring. This blog will cover derived queries, JPQL, and native queries.

Derived Queries

Derived queries are simple methods such as findBy, readBy, getBy, etc. Spring Data translates the derived queries into the JPQL (Java Persistence Query Language) query (which is then translated into SQL), making things easier for you.

To create derived queries, open the JPA repository file. The file looks similar to this:

public interface UserJpaRepository extends JpaRepository<User, Long> {

}

One thing to note is that the generic (ex: <User, Long>) takes in two type parameters. The first is the entity type (the name of the POJO class), in this case, User. The second is the type of the ID found in the POJO (since ID was declared as private Long id; in User.java, the second type parameter is Long).

You can create derived queries within the interface. Let’s say we want to obtain a list of users based on their last name. The findBy method can be used to achieve this:

public interface UserJpaRepository extends JpaRepository<User, Long> {

List<User> findByLastName(String lastName);

}

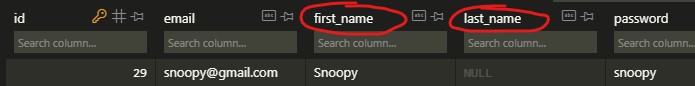

findBy<Attribute> finds the column in the table that is associated with the attribute. For example, when Spring sees findByLastName, it will look at the column that is associated with LastName. Note that SQL tables and Java have different naming conventions. When declaring a variable in Java, an uppercase letter is used to symbolize a space (ex: lastName for last name). In an SQL table’s column names, spaces are separated by a “_”.

For example, the user table’s column has first_name and last_name, not firstName and lastName. This difference is important to note, an example of this will be covered later.

Additionally, the return type of the method is List<User>. This is because there can be multiple User objects that have the last name we are looking for, so a list of users needs to be returned.

findByLastName tells Spring to look at the last_name column in the user database. Spring will then return the users that have the requested last name in a list. Something to note here is that the first letter of the attribute in the findBy method is capitalized. In this case, the “l” in findByLastName is capitalized. This tells Spring to look for the column name associated with the attribute lastName. The Spring Data JPA documentation provides an interesting read on how Spring determines the attribute from the query method.

Lastly, (String lastName) takes in a last name as an input.

findByLastName(String lastName) can be tested with an API Controller.

The API Controller class (UserApiController.java) looks like this:

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/api/users")

public class UserApiController {

@Autowired

private UserJpaRepository userRepo;

@GetMapping("/search")

public ResponseEntity<List<User>> search() {

return new ResponseEntity<>(userRepo.findByLastName("Van Pelt"), HttpStatus.OK);

}

}

The first thing we want to do in the API Controller class is to autowire the JPA repository:

@Autowired

private UserJpaRepository userRepo;

Autowire does dependency injection, which means it injects beans into the class it’s in. This is a long and interesting topic that I may write another blog post about when I have time. In simplified terms, Autowire has Spring instantiate objects so that programmers don’t need to do it themselves.

Afterwards, create an endpoint that returns the User objects with a last name of “Van Pelt” in JSON. Here, the findByLastName method (which was defined in the JPA repository) is called, with an input of “Van Pelt” as the last name. When a GET request is sent to the endpoint, Spring will search the user table for users that have a last name of “Van Pelt”.

return new ResponseEntity<>(userRepo.findByLastName("Van Pelt"), HttpStatus.OK);

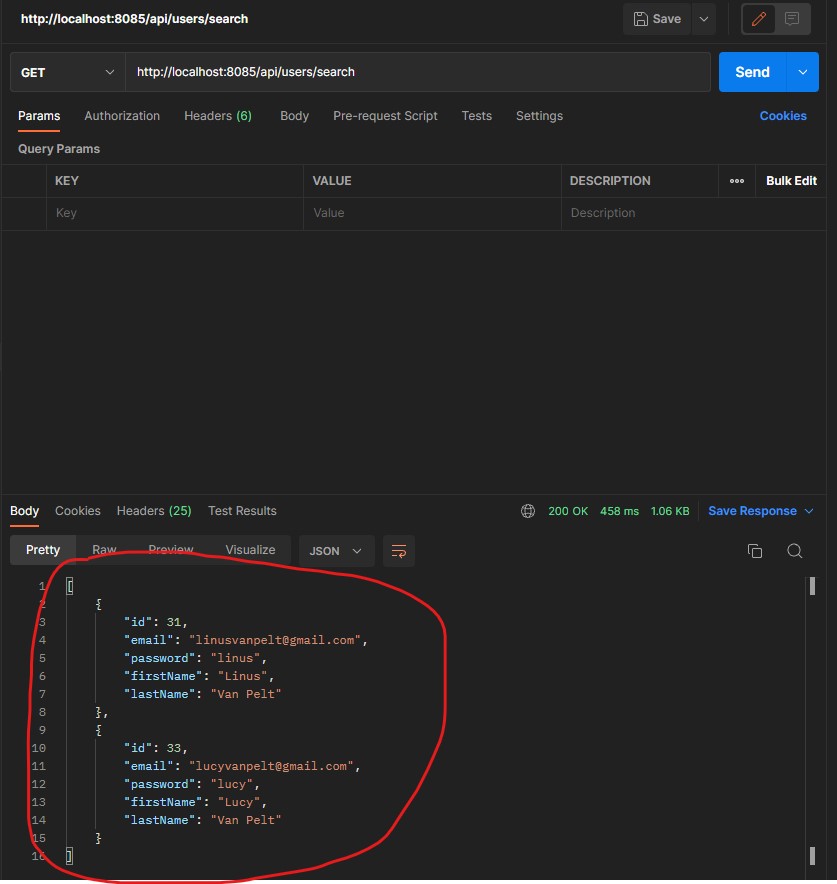

Accessing the endpoint on Postman returns the two users who have a last name of “Van Pelt”:

Other query methods

-

List<entity class> findByAttributeContaining(String a);: Returns a list of objects whose attribute has a substring that matches the input’s string -

List<entity class> findByAttributeNotNull();: Returns a list of objects whose attribute is not null

Example

JPA repository

public interface UserJpaRepository extends JpaRepository<User, Long> {

List<User> findByLastName(String lastName);

List<User> findByFirstNameContaining(String letters);

List<User> findByLastNameNotNull();

}

API Controller

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/api/users")

public class UserApiController {

@Autowired

private UserJpaRepository userRepo;

@GetMapping("/search")

public ResponseEntity<List<User>> search() {

return new ResponseEntity<>(userRepo.findByLastName("Van Pelt"), HttpStatus.OK);

}

@GetMapping("/partial")

public ResponseEntity<List<User>> partial() {

return new ResponseEntity<>(userRepo.findByFirstNameContaining("oo"), HttpStatus.OK);

}

@GetMapping("/haslastname")

public ResponseEntity<List<User>> hasLastName() {

return new ResponseEntity<>(userRepo.findByLastNameNotNull(), HttpStatus.OK);

}

}

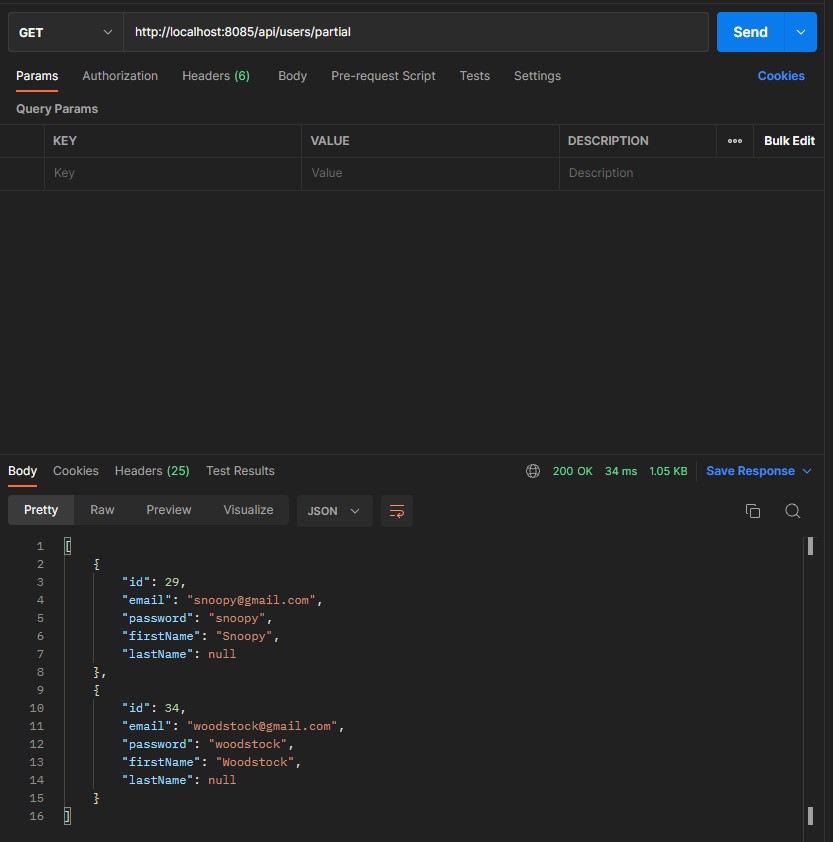

In this example, findByFirstNameContaining outputs users whose first name contains the substring “oo”:

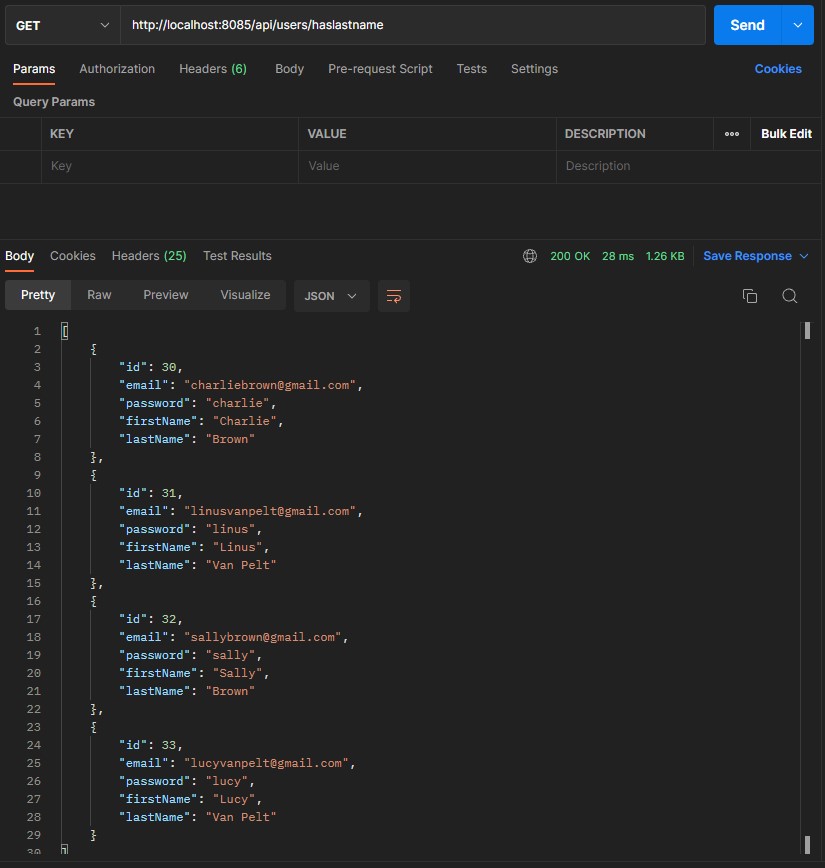

In this example, findByLastNameNotNull outputs users who have a last name:

JPQL Query

Sometimes simply creating methods using derived queries is not enough. JPQL is more flexible in that it provides a query language that looks similar to SQL. One important thing to note is that JPQL is based on entities, so JPQL queries are based on classes and attributes. JPQL queries are not based on the database tables, which makes it different from SQL. The database, however, still uses SQL. JPA implementations like Hibernate translate the JPQL query into SQL to work with the database.

Here’s an example of a JPQL query that does the same thing as findByLastName().

@Query("SELECT u FROM User u where u.lastName = ?1")

List<User> findByLastNameQuery(String lastName);

First, use the @Query annotation, and then define the query in JPQL. In this example, the query selects the User entity and finds the user objects where the user’s last name matches the input. Additionally, the u in the query is an alias for the User class. You can think of it as a variable that refers to the User class. This alias makes it quicker when referring to User in the query. The alias can be anything. For instance, “SELECT a FROM User a where a.lastName = ?1” would also work.

Next, add the method declaration after the annotation. You can name the method name (ex: findByLastNameQuery) anything.

Positional parameters and named parameters

In the query SELECT u FROM User u where u.lastName = ?1", ?1 is a positional parameter. This means that ?1 will correspond to the 1st parameter in the method (ex: lastName). So when findByLastNameQuery("Van Pelt") is called, the query becomes SELECT u FROM User u where u.lastName = 'Van Pelt'.

You can have multiple positional parameters in the query. Here is an example of searching for a user based on both first and last name:

JPA repository:

@Query("SELECT u FROM User u where u.lastName = ?1 and u.firstName = ?2")

List<User> findByName(String lastName, String firstName);

API Controller:

@GetMapping("/search")

public ResponseEntity<List<User>> search() {

return new ResponseEntity<>(userRepo.findByName("Brown", "Charlie"), HttpStatus.OK);

}

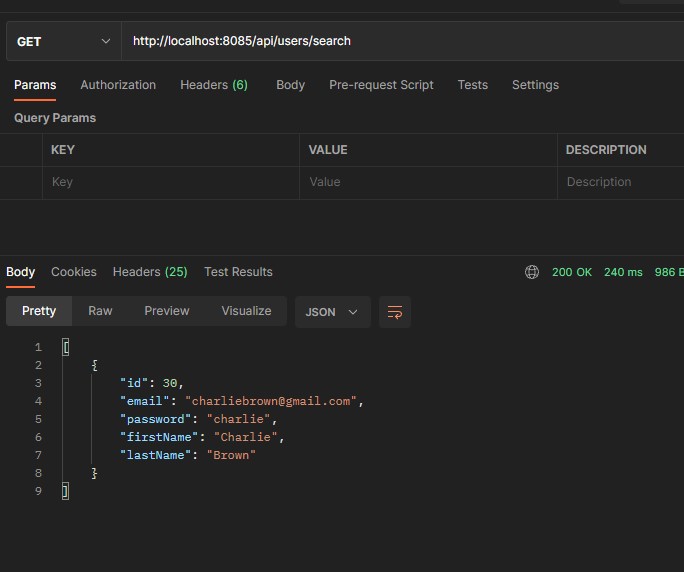

Endpoint:

You could also assign names instead of numbers to the parameters. Below is an example of using named parameters:

@Query("SELECT u FROM User u where u.lastName = :last and u.firstName = :first")

List<User> findByName(@Param("last") String lastName, @Param("first") String firstName);

Replace ?1 and ?2 with :<parameter name>, and refer to them in the method with @Param("<parameter name>").

Native Queries

While JPQL provides more flexibility than derived queries, it doesn’t have all of the features of SQL. Native queries allows the programmer to execute SQL queries. The syntax of a native query is similar to a JPQL query:

@Query(

value = "SELECT email FROM user",

nativeQuery = true

)

List<String> findEmail();

In this example, the SQL query is "SELECT email FROM user", which returns all of the emails from the email column in the database. One thing to note is that unlike JPQL, which is based on the entity class, native queries are based on the database. Therefore, native queries should use names from the database and table columns.

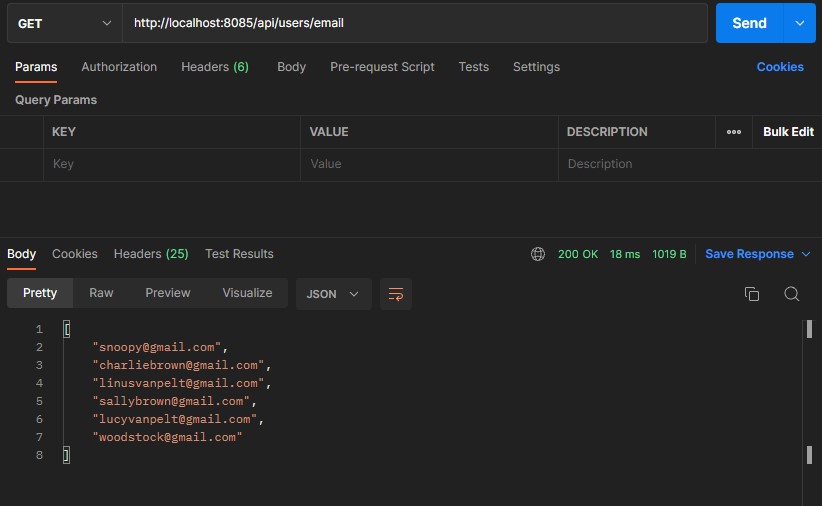

Accessing the endpoint returns a list of email strings:

Troubleshooting

While coding in Spring Boot, it is very likely that at some point you’ll encounter errors that’ll prevent you from being able to run your backend framework. While coding in Spring for this blog, I encountered many error messages. This is what I do to resolve these errors:

-

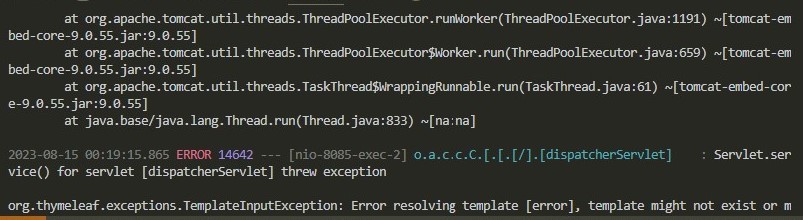

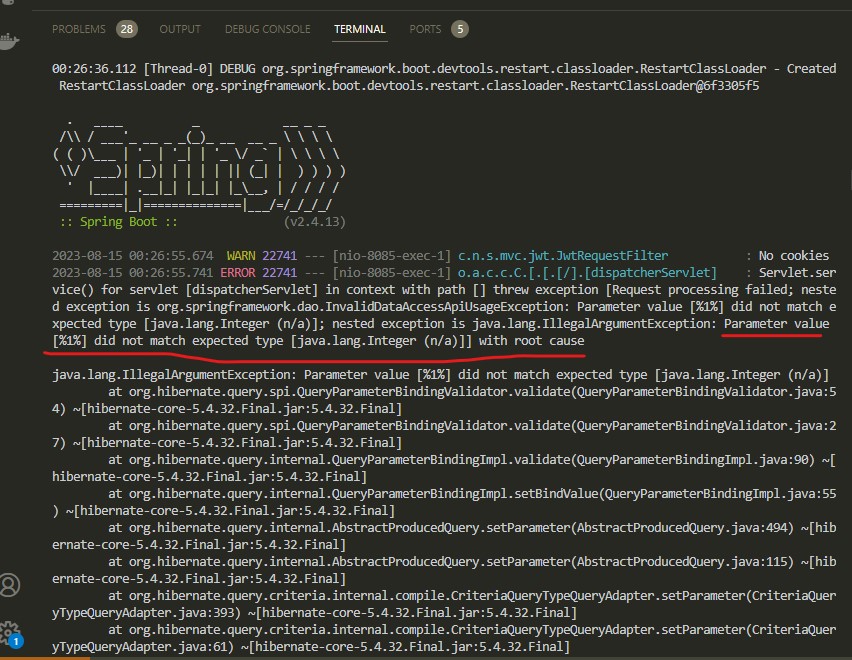

Make sure the terminal window is long enough to view the entire error message. Usually, the most important error message is at the beginning, so you’ll want to be able to scroll to the beginning of the message. One of the error messages I encountered while coding looked like this:

The error message was so long that it couldn’t fit in my terminal, so I couldn’t see the top part of the error message. I pasted the error message that occurred towards the middle of the output (similar to the the message next to the blue text in the picture) and spent a lot of time trying to figure out what was going on. I couldn’t find anything to help me fix the problem, and that was because I was searching for the wrong error.

In order to see the beginning of the output, it helps to expand your terminal. The “Spring” banner is very helpful in marking where the error message starts.

-

Copy the error and paste it into Google. ChatGPT is also a helpful tool, but it’s best to verify it by Googling. I’ve asked ChatGPT to explain some Spring Boot concepts, but found that ChatGPT provided some wrong information after double checking with Google.

-

Research. Look at StackOverflow posts where people have had similar errors. Usually, you’ll learn something new after discovering how to fix the bug. For instance, while researching the error I had, I learned that derived queries were an abstraction for JPQL queries, and I learned about Hibernate and ORM. Researching about JPQL also helped me understand more about SQL. Troubleshooting can be time consuming and requires patience, but the deeper understanding gained after figuring out the solution makes the amount of time spent into it worth it.